Models of Irrational Behaviour Shown by Economic Agents: Approaches to Regulating

Anastasia SEDOVA

Faculty of Economics, Department of Philosophy and Methodology of Economics, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russian Federation.

ABSTRACT

The goal of the article is to analyze models of irrational behavior shown by economic agents and approaches to their regulation. To achieve the goal, general and specific methods were used. Results: the paper reveals a reference, standard, and deviant model of individual behavior shown by economic agents when decision-making is determined by a complex of external and internal factors. The key approaches to regulating irrational behavior shown by economic agents are revealed using the key provisions of two concepts: behaviorist and ethological. The reasoned conclusion is that behaviorist tools can be used for simple decision-making with quick feedback and relatively easily identifiable effects. For complex decisions with no feedback and having difficult (or impossible) effect assessment, it is advisable to use cognitive ethology, which includes the tools: choice architecture and institutional design.

Keywords: behavior, economic agents, institutions, behaviorism, ethology, decision-making, economic theory, deliberate choice, institutional design.

INTRODUCTION

In fact, currently, none of the conventional and heterodox theories can fully formalize the fundamentals of particular characteristics of consumer behavior (Haider et al., 2018; Gossady et al., 2020; Vahabzadeh et al., 2020), choice, and decision-making (Yeganeh et al., 2020). In this regard, it is relevant to review the existing approaches to theory concepts, methodology, and practice of managing consumer behavior and decision-making using a multidisciplinary approach. It is based on the integration of key provisions of behavioral economics, a new institutional economic theory, and provisions in the area of neural, social, and psychological sciences.

The importance of reviewing the existing theories and practical concepts of consumer behavior management is created by a wide range of factors. One of the key factors is that the social environment influencing individual decision-making can change a rational choice for an irrational one. In the article, the thesis is revealed through the lens of behavior patterns shown by economic agents and approaches to behavior regulation. This issue was concerned by a rather wide range of scientists, including Auzan (2017), Bloom et al. (1998), Burns and Roszkowska (2018), Chakrabarti et al. (2006), Kahneman (2011), Eibl-Eibesfeldt (2017), Skinner (1988), Taler and Sunstein (2017), Thaler (2018), Veblen (2011). However, due to the continuous transformation of the socioeconomic environment in which the economic agent exists, the pattern of their consumer behavior changes as well.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

The methodology of the article involves a complex of general and specific methods. General methods include analytical and synthetic research methods, which made it possible to structure theoretical materials on the issue under consideration. Specific research methods are embodied in an analysis of socio-psychological and meta-economic data characterizing the specifics of each economic entity’s behavior pattern defined by the author and approaches to the regulation of these patterns.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

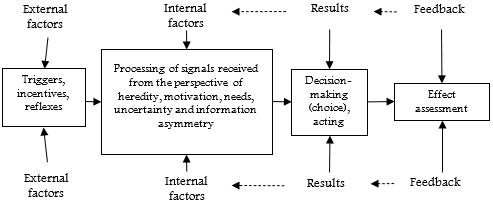

Human behavior, peculiarities of his mental activity allowing to make certain decisions, or pushing to decision-making, is a permanent area of scientific interests, from psychology and sociology to economics, including institutional, neuroeconomic, econophysics and other areas of research and development (Auzan, 2017; Bloom et al., 1998; Bowles, 2016; Chakrabarti et al., 2006). At the same time, starting from the classical economic theory emergence till T. Veblen’s works were created at the end of the 19th century (Veblen, 2011), human economic behavior has been known to be studied within the framework of a human reference model, currently known as "homo economicus". The reference model for economic agents assumes that the latter make decisions and act to maximize objective benefits (for example, maximum income or profit). Veblen (2011) criticized the reference model, proving that in fact, the institutional environment can force an economic agent to act irrationally. It is manifested in the form of conspicuous consumption, extreme hedonism, etc. In other words, external uncertainty and information asymmetry cause opportunism in the behavior of economic agents, which becomes an integral part of the standard model supplemented by the provision that under conditions of extreme uncertainty, an economic agent will primarily seek to reduce possible risks, while acting almost always irrationally. In other words, the standard model describes and explains the behavior of economic agents in the following context (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The standard model of economic agents’ individual behavior

(Compiled by the author using sources: Henry, 1991; Klyucharev et al., 2011)

In addition to the standard model, there is a deviant model describing abnormalities in the individual behavior of economic agents. It is in the deviant model that great attention is paid to the influence of institutions (rules and regulations that determine the regularity and economic agents’ regularity of the behavior). Developed formal institutions are designed to ensure public order and stability, while convergent or informal institutions must maintain that order.

But there is always room for maneuver to ensure institution evolution. At the same time, formal institutions can be destructive (in totalitarian communities, for instance) or not authoritative. In this case, divergent or informal institutions can replace formal ones, imitate them. As a rule, deviant models are applied here which could be divided into two groups (Burns and Roszkowska, 2018; Camerer, 2003; Luce, 2012):

Another group of behavioral models should be distinguished, which are formed, as a rule, in a developed and constructive institutional framework - these are protest models of behavior shown by economic agents. In other words, deviant models of behavior shown by economic agents are models that explain the causes and factors of behavioral deviations from the institutional standard. Accordingly, the behavior shown by economic agents requires to be corrected, otherwise the created social stability can be destroyed by the replication of such behavior in society.

In this latter case, scientists who are insufficiently aware of the institutional and new institutional economic theory, as well as with the achievements in neurosciences and behavioral economics, very often discuss the irrational behavior shown by economic agents. But in fact, the issue of the balance of rational and irrational behavior shown by economic agents is such a personal matter that it can be seen in the reference, in the standard, and in the deviant model. To better understand the context of the study, a definition of rational behavior shown by economic agents should be given, which will be common for any of the above-mentioned behavioral models.

Sharing R. Thaler and K. Sunstein’s point of view, we can conclude that the rational behavior shown by economic agents is characterized by the objectively evaluated (Taler and Sunstein, 2017; Thaler, 2018):

Obviously, the objectively evaluated utility of rational behavior, shown by economic agents, correlates with the concept of social justice proposed by Rawls (Rawls, 1999), that is, rational individual behavior shown by economic agents is environmentally, ethically and socially responsible decision-making, primarily forward-looking but relevant to meet current challenges (routine problems). Such behaviors can be rapidly replicated in institutionalized communities through matting signals humans. On the contrary, in institutionally underdeveloped communities, where informal institutions are more powerful than formal ones, such behavior will be seen as irrational. Therefore, to clarify the scientific position on the understanding of behavior rationality shown by economic agents, a neurological (biological and physiological) concept shall be applied.

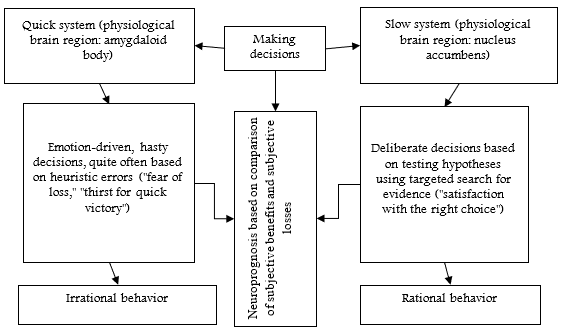

In the standard model, a decision was shown to be made by a person after information received from the outside is processed. Processing is carried out in the context of heredity, motivation, needs, uncertainty assessment, and asymmetry of information received (which is quite often unconscionable). This whole mental process is realized either through a quick or slow decision-making system (Figure 2).

Accordingly, a quick system generates irrational behavior, while a slow system generates a rational one. Since both systems were involved in the decision-making process, neuro-prognosis was applied, which is not implemented within a quick system. Thus, at this phase of the research, we conclude that irrational and rational behavior shown by economic agents is, firstly, contextual for the standard and deviant model, and, secondly, is the result of the neuro-psychosocial decision-making function. Accordingly, there is a question of the need to regulate irrational behavior, which is especially relevant to institutional communities.

Figure 2. Neuropsychological circuit of making decisions by economic agents, determining their follow-up individual behavior (Compiled by the author using sources: Kahneman, 2011; Klyucharev et al., 2011; Taler and Sunstein, 2017)

It also explains why various scientific and practical approaches to economic agents' behavior regulation developed in economically and socially developed countries where highly prioritized personal and civil liberties do not allow direct interference with individual social or economic choices. In the late XIX - early XX century, two theoretical concepts began to develop almost simultaneously, which were subsequently introduced in regulating economic agents:

The cognitive-ethological concept turned out to be more reliable and described human behavior both within the standard and within the deviant model. However, the merits of behaviorists should not be underestimated, since largely due to their research, impulsive (spontaneous) economic behavior became well-understood. It has led to the emergence and development of a new scientific area in economics - marketing, which has long used the concept of operant learning, skillfully manipulating consumers through a quick decision-making system, heightening fear of need, and increasing interest in consuming a particular product.

In addition, through a quick decision-making system, various actors impact the behavior of an economic agent: cult representatives, developers of deliberately fraudulent schemes, representatives of the legitimate and illegitimate entertainment industry, etc. But it is erroneous to believe that these factors cannot affect decision-making and create irrational behavioral models through a slow system. Studies conducting during the past ten years have repeatedly confirmed the correlation between the intelligence level and the rational behavior pattern. It means that a slow decision-making system needs continuous training, in this case, specific tools developed within the framework of the behaviorist concept can be used, for example, to:

In contrast, more sophisticated tools (choice architecture, institutional design) are advisable to be built on a cognitive-ethological concept that involves both decision-making systems to perform neurological prognosis of the effects caused by behavioral acts in those events when effects are hard to be currently identified reliably, but the future subjective expected utility can be justified for each economic agent individually. These tools are implemented through social learning, reengineering of cultural norms, formal and informal institutions, rational behavior commodification, etc.

CONCLUSIONS

To summarize and sum up the article, the following should be noted:

References

Auzan, A. (2017) Economy of everything. How institutions define our lives. Mann, Ivanov and Ferber (MYF), Moscow.

Bloom, F., Leiserson, A., & Hofstedter, L. (1988) Brain, mind and behavior. Publishing house «World», Moscow.

Bowles, S. (2016) Moral economy: why good incentives will not replace good citizens, Economic sociology, 4, 100-121.

Burns, T., & Roszkowska, E. (2018). Rational choice theory: Toward a psychological, social, and material contextualization of human choice behavior, Theoretical Economics Letters, 2, 195-207

Camerer, C. F. (2003) Strategizing in the brain, Science. 300, 1673–1675

Chakrabarti, B. K., Chakraborti, A., & Chatterjee, A. (2006) Econophysics and sociophysics: trends and perspectives. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Eibl-Eibesfeldt, I. (2017). Human ethology. Routledge, London.

Gossady, I. M., Alshehri, K. M., Aldalbahi, G. S., Alzarie, M., Alqarni, K. M. & Aldawas, A. D. (2020). Availability of Healthy Food in Different Categories of Markets. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research & Allied Sciences, 9(1), 180-186.

Haider, S., Nisar, Q. A., Baig, F., & Azeem, M. (2018). Dark Side of Leadership: Employees' Job Stress & Deviant Behaviors in Pharmaceutical Industry. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research & Allied Sciences, 7(2).

Henry, S. L. (1991) Consumers, commodities, and choices: A general model of consumer behavior, Historical Archaeology, 2, 3-14

Kahneman, D. (2011) Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan, London.

Klyucharev, V.A., Schmids, A., & Shestakova, A.N. (2011) Neuroeconomics: neuroscience of decision-making, Experimental psychology, 2, 14-35

Luce, R. D. (2012) Individual choice behavior: A theoretical analysis. Courier Corporation, New York.

Rawls, J. (1999) A Theory of Justice (2nd Edition). Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Skinner, B. F. (1988) The selection of behavior: The operant behaviorism of BF Skinner: Comments and consequences. CUP Archive.

Taler, R., & Sunstein, K. (2017) Nudge. Selection architecture. M.: Mann, Ivanov and Ferber (MYF), Moscow.

Thaler, R. (2018) New behavioral economics. Why do people violate the rules of traditional economics (Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics). EKSMO Publishing House, Moscow.

Vahabzadeh, S., Zeynali, H. & Nourali, M. (2020). Investigating the Effect of Optimal Level of Customer Stimulation on Attempting to Seek Seller Information (Case Study: Multivitamin Drugs Customers of Sobhan-Darou Iran). Archives of Pharmacy Practice, 10(1), 128-135.

Veblen, T. (2011) Theory of the idle class (Çev.: S. Sorokina). Publishing house «LIBROCOM», Moscow.

Yeganeh, E. M., Hamedi, O., Torabi, M., Yeganeh, A. M. & Badri, E. (2020). Brand Gender and Consumer Brand Equity: The Mediating Role of Consumer Brand Engagement and Brand Love. Archives of Pharmacy Practice, 11(1), 177-185.

Auzan, A. (2017) Economy of everything. How institutions define our lives. Mann, Ivanov and Ferber (MYF), Moscow.

Bloom, F., Leiserson, A., & Hofstedter, L. (1988) Brain, mind and behavior. Publishing house «World», Moscow.

Bowles, S. (2016) Moral economy: why good incentives will not replace good citizens, Economic sociology, 4, 100-121.

Burns, T., & Roszkowska, E. (2018). Rational choice theory: Toward a psychological, social, and material contextualization of human choice behavior, Theoretical Economics Letters, 2, 195-207

Camerer, C. F. (2003) Strategizing in the brain, Science. 300, 1673–1675

Chakrabarti, B. K., Chakraborti, A., & Chatterjee, A. (2006) Econophysics and sociophysics: trends and perspectives. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Eibl-Eibesfeldt, I. (2017). Human ethology. Routledge, London.

Gossady, I. M., Alshehri, K. M., Aldalbahi, G. S., Alzarie, M., Alqarni, K. M. & Aldawas, A. D. (2020). Availability of Healthy Food in Different Categories of Markets. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research & Allied Sciences, 9(1), 180-186.

Haider, S., Nisar, Q. A., Baig, F., & Azeem, M. (2018). Dark Side of Leadership: Employees' Job Stress & Deviant Behaviors in Pharmaceutical Industry. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research & Allied Sciences, 7(2).

Henry, S. L. (1991) Consumers, commodities, and choices: A general model of consumer behavior, Historical Archaeology, 2, 3-14

Kahneman, D. (2011) Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan, London.

Klyucharev, V.A., Schmids, A., & Shestakova, A.N. (2011) Neuroeconomics: neuroscience of decision-making, Experimental psychology, 2, 14-35

Luce, R. D. (2012) Individual choice behavior: A theoretical analysis. Courier Corporation, New York.

Rawls, J. (1999) A Theory of Justice (2nd Edition). Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Skinner, B. F. (1988) The selection of behavior: The operant behaviorism of BF Skinner: Comments and consequences. CUP Archive.

Taler, R., & Sunstein, K. (2017) Nudge. Selection architecture. M.: Mann, Ivanov and Ferber (MYF), Moscow.

Thaler, R. (2018) New behavioral economics. Why do people violate the rules of traditional economics (Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics). EKSMO Publishing House, Moscow.

Vahabzadeh, S., Zeynali, H. & Nourali, M. (2020). Investigating the Effect of Optimal Level of Customer Stimulation on Attempting to Seek Seller Information (Case Study: Multivitamin Drugs Customers of Sobhan-Darou Iran). Archives of Pharmacy Practice, 10(1), 128-135.

Veblen, T. (2011) Theory of the idle class (Çev.: S. Sorokina). Publishing house «LIBROCOM», Moscow.

Yeganeh, E. M., Hamedi, O., Torabi, M., Yeganeh, A. M. & Badri, E. (2020). Brand Gender and Consumer Brand Equity: The Mediating Role of Consumer Brand Engagement and Brand Love. Archives of Pharmacy Practice, 11(1), 177-185.